How to Know When You Have a Viris on Xt

Abstract

We report temporal patterns of viral shedding in 94 patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-xix and modeled COVID-nineteen infectiousness profiles from a separate sample of 77 infector–infectee manual pairs. We observed the highest viral load in throat swabs at the time of symptom onset, and inferred that infectiousness peaked on or before symptom onset. We estimated that 44% (95% conviction interval, 30–57%) of secondary cases were infected during the index cases' presymptomatic phase, in settings with substantial household clustering, active instance finding and quarantine outside the home. Illness control measures should be adjusted to account for probable substantial presymptomatic transmission.

Main

SARS-CoV-ii, the causative agent of COVID-19, spreads efficiently, with a basic reproductive number of two.2 to ii.5 determined in Wuhan1,ii. The effectiveness of command measures depends on several key epidemiological parameters (Fig. 1a), including the series interval (duration betwixt symptom onsets of successive cases in a transmission chain) and the incubation period (time between infection and onset of symptoms). Variation between individuals and transmission chains is summarized past the incubation menstruum distribution and the serial interval distribution, respectively. If the observed mean series interval is shorter than the observed hateful incubation period, this indicates that a meaning portion of transmission may accept occurred before infected persons have developed symptoms. Significant presymptomatic transmission would probably reduce the effectiveness of command measures that are initiated by symptom onset, such equally isolation, contact tracing and enhanced hygiene or use of face masks for symptomatic persons.

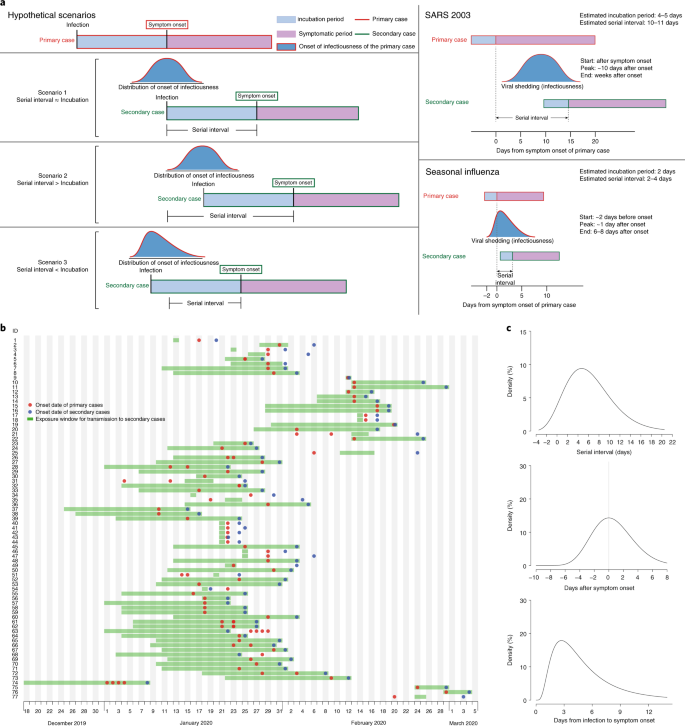

a, Schematic of the relation between dissimilar time periods in the transmission of infectious illness. b, Man-to-man manual pairs of SAR-CoV-2 virus (Due north = 77). We assumed a maximum exposure window of 21 days prior to symptom onset of the secondary cases. Detailed information on the manual pairs and the source of information is summarized in Supplementary Tables 2 and iii. c, Estimated serial interval distribution (top), inferred infectiousness profile (middle) and causeless incubation period (bottom) of COVID-19.

SARS (astringent acute respiratory syndrome) was notable, because infectiousness increased around 7–ten days later symptom onsetthree,4. Onward transmission can be substantially reduced by containment measures such as isolation and quarantine (Fig. 1a)5. In contrast, flu is characterized by increased infectiousness shortly effectually or even before symptom onset6.

In this report, we compared clinical data on virus shedding with separate epidemiologic data on incubation periods and serial intervals between cases in transmission chains, to depict inferences on infectiousness profiles.

Amid 94 patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 admitted to Guangzhou Eighth People'due south Hospital, 47/94 (50%) were male person, the median age was 47 years and 61/93 (66%) were moderately sick (with fever and/or respiratory symptoms and radiographic bear witness of pneumonia), just none were classified equally 'astringent' or 'critical' on hospital admission (Supplementary Table 1).

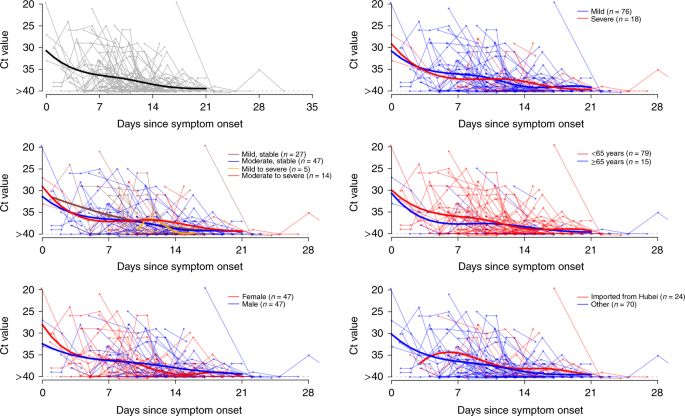

A total of 414 pharynx swabs were collected from these 94 patients, from symptom onset up to 32 days afterwards onset. Nosotros detected loftier viral loads soon after symptom onset, which then gradually decreased towards the detection limit at about solar day 21. There was no obvious difference in viral loads beyond sex, historic period groups and affliction severity (Fig. 2).

Viral load (threshold cycle (Ct) values) detected by RT–PCR (PCR with reverse transcription) in throat swabs from patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 (N = 94), overall and stratified past disease severity, sexual practice, age group and link to Hubei province. The detection limit was Ct = 40, which was used to indicate negative samples. The thick lines show the trend in viral load, using smoothing splines. We added some noise to the data points to avoid overlaps.

Separately, based on 77 transmission pairs obtained from publicly available sources within and outside mainland Mainland china (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Tabular array 2), the series interval was estimated to accept a hateful of 5.8 days (95% confidence interval (CI), 4.8–half-dozen.8 days) and a median of five.2 days (95% CI, four.1–half dozen.4 days) based on a fitted gamma distribution, with 7.vi% negative series intervals (Fig. 1c). Assuming an incubation period distribution of hateful 5.two days from a separate study of early COVID-19 cases1, we inferred that infectiousness started from 12.3 days (95% CI, v.9–17.0 days) earlier symptom onset and peaked at symptom onset (95% CI, –0.ix–0.nine days) (Fig. 1c). We further observed that only <0.1% of transmission would occur earlier vii days, 1% of transmission would occur before five days and 9% of transmission would occur before 3 days prior to symptom onset. The estimated proportion of presymptomatic transmission (area under the curve) was 44% (95% CI, thirty–57%). Infectiousness was estimated to decline quickly within 7 days. Viral load data were not used in the estimation simply showed a similar monotonic decreasing blueprint.

In sensitivity analysis, using the same estimating procedure but holding constant the start of infectiousness from 5, 8 and 11 days earlier symptom onset, infectiousness was shown to peak at ii days before to one twenty-four hours after symptom onset, and the proportion of presymptomatic transmission ranged from 37% to 48% (Extended Information Fig. 1).

Finally, simulation showed that the proportion of short serial intervals (for case, <2 days) would be larger if infectiousness were assumed to commencement before symptom onset (Extended Data Fig. 2). Given the 7.6% negative serial intervals estimated from the infector–infectee paired data, kickoff of infectiousness at least ii days earlier onset and meridian infectiousness at two days before to 1 day after onset would be nigh consistent with this observed proportion (Extended Data Fig. 3).

Here, we used detailed data on the timing of symptom onsets in transmission pairs to infer the infectiousness contour of COVID-19. Nosotros showed substantial transmission potential before symptom onset. Of note, most cases were isolated after symptom onset, preventing some post-symptomatic manual. Even college proportions of presymptomatic manual of 48% and 62% have been estimated for Singapore and Tianjin, where active instance finding was implemented7. Places with active case finding would tend to have a higher proportion of presymptomatic transmission, mainly due to quick quarantine of shut contacts and isolation, thus reducing the probability of secondary spread afterwards in the grade of illness. In a rapidly expanding epidemic wherein contact tracing/quarantine and perhaps even isolation are no longer viable, or in locations where cases are not isolated outside the home, we should therefore observe a lower proportion of presymptomatic transmission.

Our analysis suggests that viral shedding may begin five to vi days before the appearance of the kickoff symptoms. Afterward symptom onset, viral loads decreased monotonically, consequent with ii recent studiesviii,9. Some other study from Wuhan reported that virus was detected for a median of 20 days (up to 37 days amongst survivors) after symptom onset10, just infectiousness may decline significantly 8 days after symptom onset, as live virus could no longer exist cultured (according to Wölfel and colleagues11). Together, these results support our findings that the infectiousness contour may more closely resemble that of flu than of SARS (Fig. 1a), although we did not have data on viral shedding before symptom onset6,12. Our results are also supported by reports of asymptomatic and presymptomatic manualthirteen,14.

For a reproductive number of 2.5 (ref. 2), contact tracing and isolation lonely are less likely to exist successful if more than than 30% of transmission occurred before symptom onset, unless >90% of the contacts can be traced15. This is more likely doable if the definition of contacts covers 2 to 3 days prior to symptom onset of the index case, equally has been done in Hong Kong and mainland People's republic of china since late February. Even when the control strategy is shifting abroad from containment to mitigation, contact tracing would still be an important measure, such every bit when there are super-spreading events that may occur in high-hazard settings including nursing homes or hospitals. With a substantial proportion of presymptomatic transmission, measures such as enhanced personal hygiene and social distancing for all would probable be the key instruments for community disease control.

Our study has several limitations. Offset, symptom onset relies on patient remember after confirmation of COVID-19. The potential recall bias would probably accept tended toward the direction of nether-observation, that is, filibuster in recognizing beginning symptoms. Equally long as these biases did non differ systematically between infector and infectee, the serial interval estimate would non be substantially affected. However, the incubation period would accept been overestimated, and thus the proportion of presymptomatic manual artifactually inflated. 2d, shorter serial intervals than those reported here have been reported, simply such estimates diffuse when restricted to infector–infectee pairs with more than certain transmission linksxvi. Finally, the viral shedding dynamics were based on data for patients who received treatment according to nationally promulgated protocols, including combinations of antivirals, antibiotics, corticosteroids, immunomodulatory agents and Chinese medicine preparations, which could have modified the shedding dynamical patterns.

In decision, we take estimated that viral shedding of patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 peaked on or before symptom onset, and a substantial proportion of manual probably occurred earlier first symptoms in the index case. More inclusive criteria for contact tracing to capture potential transmission events ii to 3 days before symptom onset should exist urgently considered for constructive control of the outbreak.

Methods

Sources of data

Guangzhou Eighth People's Hospital in Guangdong, China was designated as i of the specialized hospitals for treating patients with COVID-19 at both city and provincial levels on xx Jan 2020. After that, many people with COVID-nineteen were admitted via fever clinics, the hospital emergency room or afterwards confirmation of cases from community epidemiological investigation carried out by the Guangzhou Center for Disease Control and Prevention, or transferred from other hospitals. The showtime confirmed patient with COVID-nineteen was admitted on 21 January 2020, only in the initial phase, patients suspected to take COVID-xix were also admitted. We identified all suspected and confirmed COVID-19 cases admitted from 21 Jan 2020 to fourteen February 2020 and collected throat swabs in each instance. Patients included those who traveled from Wuhan or Hubei to Guangzhou likewise as locals, with cases ranging from asymptomatic, mild to moderate at admission.

The samples were tested by N-factor-specific quantitative RT–PCR assay as previously described17. To sympathise the temporal dynamics of viral shedding and exclude non-confirmed COVID-nineteen cases, we selected 94 patients who had at to the lowest degree one positive result (bike threshold (Ct) value < forty) in their pharynx samples. Serial samples were collected from some but not all patients for clinical monitoring purposes.

We collected data reported on possible human being-to-human manual pairs of patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-xix from publicly available sources, including announcements made by government health agencies and media reports in mainland Mainland china and countries/regions outside People's republic of china. A manual pair was defined as two confirmed COVID-19 cases identified in the epidemiologic investigation past showing a clear epidemiologic link with each other, such that one case (infectee) was highly likely to take been infected by the other (infector), by fulfilling the post-obit criteria: (1) the infectee did not written report a travel history to an area affected past COVID-xix or any contact with other confirmed or suspected COVID-19 cases except for the infector inside 14 days before symptom onset; (two) the infector and infectee were not identified in a patient cluster where other COVID-19 cases had too been confirmed; and (3) the infector and infectee pair did non share a common source of exposure to a COVID-nineteen case or a place where in that location were COVID-19 case(s) reported. Nosotros excluded possible transmission pairs without a articulate exposure history reported prior to symptom onset. Information of possible transmission pairs of COVID-xix were extracted, including historic period, sex, location, engagement of symptom onset, type or relationship between the pair cases and time of contact of the cases.

Statistical analysis

Nosotros analyzed two separate information sets—clinical and epidemiologic—to assess presymptomatic infectiousness. First, we assessed longitudinal viral shedding data from patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 starting from symptom onset, where viral shedding during the first few days afterwards illness onset could be compared with the inferred infectiousness. Second, the serial intervals from articulate transmission chains, combined with information on the incubation period distribution, were used to infer the infectiousness contour, equally described in the following.

We nowadays SARS-CoV-2 viral loads in the pharynx swabs of each patient past mean solar day of symptom onset. To aid visualization, a smoothing spline was fitted to the Ct values to summarize the overall trend. Specifically, a generalized additive model, E(Y) =β 0 +due south(t), with an identity link was fitted, where Y are the Ct values, β 0 is the intercept and s(t) is a cubic spline evaluated at t days after symptom onset. We besides compared the viral load by illness severity, age, sex and travel history from Hubei.

We fitted a gamma distribution to the transmission pairs data to estimate the serial interval distribution. Nosotros used a published estimate of the incubation period distribution to infer infectiousness with respect to symptom onset from the first 425 patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan with detailed exposure historyi. We considered that infected cases would become infectious at a certain fourth dimension point before or later on illness onset (t S1). Infectiousness—that is, transmission probability to a secondary case—would and then increase until reaching its meridian (Fig. one). The manual outcome would occur at time t I with a probability described by the infectiousness profile β c (t I −t S1) relative to the illness onset appointment, assuming a gamma distribution β(t) with a fourth dimension shift c to allow for start of infectiousness c days prior to symptom onset; that is, β c (t) =β(t +c). The secondary case would then evidence symptoms at time t S2, after the incubation catamenia that is assumed to follow a lognormal distribution g(t S2 −t I). Hence the observed serial intervals distribution f(t S2 −t S1) would be the convolution between the infectiousness profile and incubation period distribution. Nosotros constructed a likelihood role based on the convolution, which was fitted to the observed serial intervals, allowing for the start of infectiousness around symptom onset and window of symptom onset (t S1l, t S1u), given past

$$L\left( {t_{\rm{S1u}},t_{\rm{S1l}},t_{\rm{S2}}|\theta } \right) = \mathop {\int}\limits_{t_{\rm{S1l}}}^{t_{\rm{S1u}}} {\mathop {\int}\limits_{ - \infty }^{t_{\rm{S}2}} {\beta _c} } \left( {t_{\rm{I}} - t_{\rm{S}1}} \right)yard(t_{\rm{South}two} - t_{\rm{I}}){\rm{d}}t_{\rm{I}}{\rm{d}}t_{\rm{S}i}$$

A normalization factor can be added to account for the uncertainty in the symptom-onset dates of the alphabetize cases. Assuming a uniform distribution, the likelihood would differ only by a multiplicative abiding and requite the aforementioned estimates.

Parameters θ, including the gamma distribution parameters and the start of infectiousness, were estimated using maximum likelihood. The 95% CIs were obtained past bootstrapping with 1,000 replications. We also performed sensitivity analyses by fixing the start of infectiousness from days 5, 8 and xi before symptom onset and inferred the infectiousness profile.

Every bit an boosted check, nosotros simulated the expected serial intervals assuming the aforementioned same incubation period simply two different infectiousness profiles, where infectiousness started on the same mean solar day and from two days earlier symptom onset, respectively. A contempo written report isolated alive infectious SARS-CoV-two virus from patients with COVID-xix upward to 8 days after symptom onseteleven, thus we assumed the same duration of infectiousness. We also assumed that infectiousness peaked on the day of symptom onset. The timing of transmission to secondary cases was simulated according to the infectiousness profile using a lognormal and exponential distribution, respectively, where the serial intervals were estimated as the sum of the onset to transmission interval and the incubation period. We drew random samples for the manual time relative to symptom onset of the infector T I ≈β c (t), and also the incubation flow T inc ≈f(t), and so the simulated serial interval was T I +T inc. We also performed simulation considering combinations of different infectiousness profiles, with start of infectiousness vii days before to 3 days after symptom onset, and top infectiousness also vii days before to 3 days after symptom onset. Nosotros present the distribution of the serial intervals and proportion of negative series intervals over 10,000 simulations.

All statistical analyses were conducted in R version 3.6.3 (R Development Core Squad).

Ideals approval

Information drove and analysis were required by the National Wellness Committee of the People's Republic of China to be part of a continuing public health outbreak investigation.

Reporting Summary

Farther information on research design is bachelor in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Detailed transmission pairs data in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information and viral shedding data volition exist available upon asking and approval by a data access commission. The information access commission comprises leadership of the Guangzhou Eighth People's Infirmary and the Guangzhou Wellness Committee. There is no restriction to data admission.

Code availability

Nosotros provided the lawmaking for generating Fig. 1c in the Supplementary Information and at https://github.com/ehylau/COVID-19. Other codes are bachelor upon request to the corresponding writer.

Change history

-

07 August 2020

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-1016-z

References

-

Li, Q. et al. Early manual dynamics in Wuhan, People's republic of china, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. North. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1199–1207 (2020).

-

Wu, J. T., Leung, Chiliad. & Leung, G. M. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling written report. Lancet 395, 689–697 (2020).

-

Peiris, J. S. et al. Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia: a prospective written report. Lancet 361, 1767–1772 (2003).

-

Pitzer, 5. Eastward., Leung, M. One thousand. & Lipsitch, 1000. Estimating variability in the manual of severe acute respiratory syndrome to household contacts in Hong Kong, China. Am. J. Epidemiol. 166, 355–363 (2007).

-

Riley, S. et al. Transmission dynamics of the etiological amanuensis of SARS in Hong Kong: affect of public health interventions. Scientific discipline 300, 1961–1966 (2003).

-

Ip, D. K. et al. Viral shedding and manual potential of asymptomatic and paucisymptomatic influenza virus infections in the community. Clin. Infect. Dis. 64, 736–742 (2017).

-

Ganyani, T. et al. Estimating the generation interval for COVID-19 based on symptom onset data. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.05.20031815 (2020).

-

Zou, L. et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1177–1179 (2020).

-

To, 1000.Thou.-W. et al. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibiotic responses during infection by SARS-CoV-ii: an observational cohort report. Lancet Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/x.1016/S1473-3099(twenty)30196-1 (2020).

-

Zhou, F. et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-nineteen in Wuhan, Cathay: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 395, 1054–1062 (2020).

-

Wölfel, R. et al. Virological cess of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x (2020).

-

Tsang, T. Chiliad. et al. Flu A virus shedding and infectivity in households. J. Infect. Dis. 212, 1420–1428 (2015).

-

Bai, Y. et al. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-xix. JAMA https://doi.org/x.1001/jama.2020.2565 (2020).

-

Tong, Z. D. et al. Potential presymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-ii, Zhejiang Province, Mainland china, 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis.https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2605.200198 (2020).

-

Hellewell, J. et al. Feasibility of controlling COVID-19 outbreaks by isolation of cases and contacts. Lancet Glob. Health 8, e488–e496 (2020).

-

Nishiura, H., Linton, N. Thousand. & Akhmetzhanov, A. R. Serial interval of novel coronavirus (COVID-xix) infections. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 93, 284–286 (2020).

-

Chen, W. et al. Detectable 2019-nCoV viral RNA in blood is a strong indicator for the further clinical severity. Emerg. Microbes Infect. ix, 469–473 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Section of Science and Technology of Guangdong Province (project no. 2020B111108001, to F.L.) and a deputed grant from the Health and Medical Inquiry Fund from the Authorities of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (to B.J.C.).

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

Ten. He, Due east.H.Y.L., P.W., B.J.C., F.L. and G.One thousand.L. conceived and designed the study. X. He, X.D., J.W., Y.G., Ten.T., X.M., Y.C. and B.L. were responsible for clinical care and collected all biomaterials. W.C. and F.H. carried out laboratory testing. Q.Z., M.Z. and Y.West. collected and collated linked clinical–epidemiologic data. L.Z., F.Z. and F.L. supervised and coordinated all aspects of the study at Guangzhou Eighth People's Hospital. P.Due west., X. Hao, Y.C.L. and J.Y.W. collected and verified all infector–infectee transmission data. Due east.H.Y.L., B.J.C. and G.M.L. wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to information interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript and approved the concluding version of the manuscript.

Respective author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Alison Farrell and João Monteiro were the primary editors on this article and managed its editorial process and peer review in collaboration with the rest of the editorial team.

Publisher's annotation Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. ane Inferred infectiousness profile.

Infectiousness was assumed to commencement from 5 days (top) to 8 days (centre) and xi days (bottom) before symptom onset.

Extended Information Fig. 2 Fake series intervals.

Simulated serial intervals bold infectiousness started on the same solar day of symptom onset (top console) and from two days before symptom onset (bottom console) to nearly 10 days afterward symptom onset. Both scenarios assumed that infectiousness peaked on the outset day of symptom onset.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Simulated proportions of negative serial intervals.

Simulated proportions of negative series intervals bold beginning of infectiousness and peak infectiousness from vii days before symptom onset to 3 days after symptom onset. From the estimated serial interval distribution based on infector-infectee pairs, vii.six% of the serial intervals were negative. Grayness surface area represents the implausible range where the meridian infectious is before than the start of infectiousness.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

He, X., Lau, E.H.Y., Wu, P. et al. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat Med 26, 672–675 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

Issue Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5

Further reading

villarrealtwordor.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-020-0869-5

0 Response to "How to Know When You Have a Viris on Xt"

Post a Comment